in the thick of it

- Joshua Shelov

- Mar 25, 2017

- 6 min read

On Wednesday afternoon, just past 3pm, I was standing on the Hungerford Bridge over the Thames River, taking touristy pictures of Parliament, Big Ben, and the London Eye.

At 3:07pm, I took this picture:

The picture was a little dark, so I futzed with the settings a bit, lightened it up, and raised my phone to take one more.

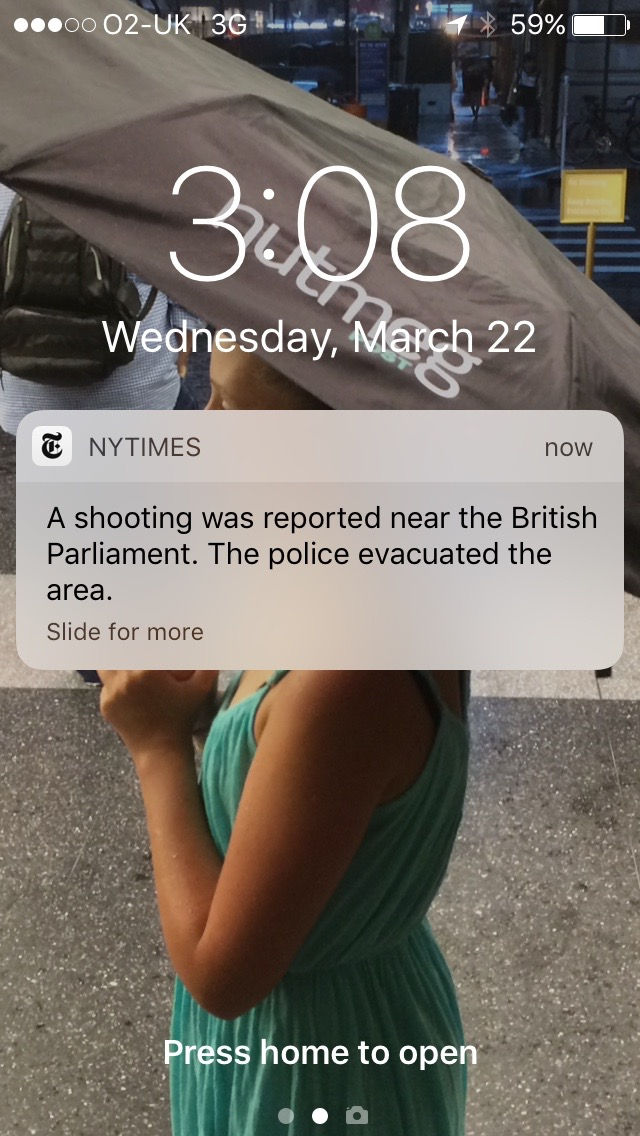

Suddenly an NY Times alert popped up on my home screen:

I can’t quite explain exactly what I felt in that moment.

I heard no screams nor sirens. I knew nothing about the full extent of the attack. All I knew was: shooting, Parliament. And there I was, looking at Parliament.

My wife called.

“Are you OK?”

“Yeah, but I’m actually standing right here. I can see Parliament.”

“Well, they’re saying terrorist attack on the radio. Some guy stabbed a cop and they shot him.”

“Are you serious?”

“Yeah, why don’t you maybe get the hell out of there.”

“OK.”

I hung up the phone.

And I started walking towards Parliament.

I’m sure there’s some wise old German word, something in the vein of schadenfreude, for the strange, stupid thrill one feels when you’re smack in the middle of a tragedy. I’m sure I would have felt differently if I’d actually heard gunshots, or felt signs of actual panic. But in that moment, armed only with two pieces of information - the Times alert and my wife’s phone call - I felt strangely calm and safe.

I remember doing a bit of absurd law-of-averages calculus in my head: Well, the attack is over, right? Madman, stabbing, shot dead. Sounds like a lone nut to me. So then, technically, aren’t I in kind of the safest place in the world right now? Isn’t the likelihood of another attack, right here right now, sort of like the odds of lightning striking the same place twice?

I walked south along the western bank of the Thames, towards Parliament. The water was on my left. My path was the dark green line:

The commotion thickened as I got closer. Everyone’s necks were craning south. People were chatting and whispering, walking quickly in both directions. I exchanged hearsay with a young couple - a mocha-skinned man and an ultra-pale girl. They knew just about as much as I did.

Two hundred yards north of Parliament, give or take, I reached the blue line of police tape: do not cross. (In London, it’s blue.) End of the line.

I didn't so much as glance to my left, at Westminster Bridge. I didn’t yet know about that piece of the attack. All I knew was what I knew, so I just stared at Parliament, from my spot behind the police tape: a dork outside the velvet rope.

Nothing to see here. I turned around and started walking back from whence I came. I needed to be across the river, at the London Eye, to meet my colleague at 4 o’clock. It was a bit past 3:30.

Then I came upon a terrible sight - a woman having a seizure on the sidewalk. She was surrounded by seven or eight amateur Good Samaritans. Medical professionals had not yet arrived.

I did another piece of mental calculus. Was I needed here? Could I help? What could I do?

I stopped and stared and tried to assess the expertise of the people gathered around her. The woman was crying out in pain. She was young, maybe 20 years old. Maybe this wasn’t a seizure. How the hell should I know.

One of the people kneeling by her was an Indian/Pakistani/South Asian woman who seemed to have taken charge. Perhaps she was a doctor, or CPR-trained: either way, she was right in the thick of it, wrapping insulating jackets and sweaters around the legs of the wailing woman.

To my right, someone else was on the phone, giving coordinates to the 911-operator. Oh hey: it was the mocha-skinned guy I had chatted with a few minutes before. And there, on the ground, was his ultra-pale companion. She wasn’t in charge - that was the Indian woman - but she was right in there, stroking the wailing woman’s face and hair, hands right on the situation.

What should I do? Was I extraneous? Was there a missing layer of help I could provide? In the slow-motion of the moment, I felt like there was nothing I could do. I stood still, dumbly, morally unsure about what to do.

I glanced around at the wider scene. I remember thinking - wow, look: there are people who aren’t even stopping. They’re clearly hearing this woman in pain, glancing down and seeing her even. But they’re not even slowing down.

They’re even worse than me.

Suddenly a big chap started bellowing, “Everyone back up please, unless you’re helping, please give her some room.” I made my decision. I should go. I was not a value-add. Indian woman was running the show. 911 was coming.

I chose to walk on.

I crossed back over the Hungerford Bridge, and walked down the eastern bank of the river, towards the London Eye (the big Ferris-wheel thingy).

My colleague Charlotte and I were scheduled to ride the Eye together with our cinematographer. (Charlotte is a tad publicity-shy, so I am changing her name.) She and I are in the midst of producing a documentary. Our plan had been to take our camera into one of the Eye-carriages, and film the city from on high.

That was not to be. The Eye had been shut down because of the incident. As I approached the base of the Eye, I looked up and saw that roughly half the carriages were empty. Half were full: their inhabitants pressed up against the glass like zoo animals. It appeared as if an evacuation process had begun, and then been halted. The Eye was at a standstill.

I saw Charlotte. She is a highly no-bullshit 30-something year-old, just starting to spread her wings in a producing career that will likely win her many Emmys. She is all business and suffers no fools. Charlotte was kind of made for moments like this.

Charlotte was standing with a 70-ish-year-old-woman I did not know: Josh, meet Beth. She's from Winnipeg. Beth had three daughters and a sister stuck up there. Beth was afraid of heights, and thus had passed on the ride an hour earlier. You kids go on ahead. I’ll meet up with you later.

Now here she was, alone, down below, separated from her children, quite anxious, but in a contained, Canadian kind of way. Charlotte had sensed Beth’s fear, like a fox to a scent. Charlotte told me matter-of-factly that she wasn’t going anywhere until Beth got her family back. That’s pretty much all you need to know about Charlotte.

I guess that means I wasn’t going anywhere either, right?

I almost smiled at the moral comfort of it all. Would I have stayed with Beth, had I come upon her first, instead of Charlotte? If I’m honest with myself, I’d have to say, probably not. I certainly can't say that I would have had the requisite antennae to have sensed Beth's fear. But now that Charlotte had found her, and pitched a moral tent by her side, it was relatively easy for me to hang in there, too. I could even bask in a bit of reflected valor. Of course I would hang in there now, too. How could I leave? Of course I wouldn’t. I zipped up my coat, spotted a food truck, and asked Beth if she’d like a cup of tea. Yes, thank you, that’s very kind. Milk and one sugar.

So we spent the afternoon together, looking up occasionally, chatting about Trump, Canada, London, refugees. Beth was in contact with her kids by phone, so we knew that they were OK up there. We scrutinized the slow-moving, yellow-vested London MP’s, milling around the base of the Eye. We wondered why the evacuation was taking so long. We shared with each other our mildly queasy wonderings about whether or not the incident was actually, verifiably over. The Eye was an awfully ripe target, was it not? That was probably why they halted the evacuation, right - to make absolutely sure that they could study every conceivable shred of threat-evidence: on the ground, up in the carriages, in the gears of the contraption itself, etc.

We had no goddamn idea what we were speculating about, of course. We just waited, chatted, and waited some more.

Friends and colleagues from home pinged our phones all afternoon. Are you OK? Stay safe! My dad texted: Jen said you’re still at Parliament. Get the hell out of there. Now.

It was almost six o’clock when the Eye finally started moving again. We had been there for two hours. The sun was almost gone, leaving long, squinty shadows. Carriage by carriage the Eye unloaded. Beth’s family, true to Murphy’s Law, was one of the last to disembark.

And then there they were. Beth gasped and waved as she saw her daughters, who waved back frantically, some fifty feet away, before quickly being led away by MP’s. They vanished into a nearby silo.

Fortunately, an MP came straight over to Beth. Charlotte had arranged this. The MP lifted the police tape and extended a hand to Beth, to lead her to her loved ones.

Beth gave Charlotte a meaningful goodbye embrace. She even threw me a little sidekick attaboy. Thanks for the tea.

And then she was off, into the silo, and the arms of her daughters, her heart sliced with a paper cut of the deepest kind of fear, its residue and staying power TBD.

[to subscribe to this blog, type your email address into the form at the bottom of this page.]

Comments